“Oh, pray for the peace of Jerusalem; they shall prosper that love thee.” ~ Psalm 122:16

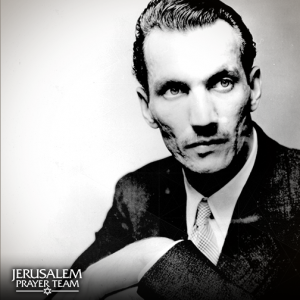

That simple directive from Psalm 122 was inscribed on the interior side of a ring worn by Anthony Ashley-Cooper, better known in the pages of history as the 7th Earl of Shaftesbury. One of the things for which the philanthropic British aristocrat is most noted is being distinguished as the first major politician to put forth a definitive proposal for the creation of a Jewish homeland, which he did in 1839. However, that is not entirely true.

The first politician known to have suggested restoring the Jewish people to the Land of Promise was actually Napoleon Bonaparte, but it was his notion that eventually caught the attention of Lord Shaftesbury. In Napoleon’s quest to restore the empire of Alexander the Great, he realized that Jerusalem and the surrounding area was a lynch-pin for maintaining political and economic stability in the region over which he wished to rule. The master strategist made a proposal to the Jews:

“[France] offers to you at this very time, and contrary to all expectations, Israel’s patrimony. Rightful heirs of Palestine – hasten! Now is the moment which may not return for thousands of years, to claim the restoration of your rights among the population of the universe which had shamefully withheld from you for thousands of years, your political existence as a nation among the nations, and the unlimited natural right to worship Jehovah in accordance with your faith, publicly and in likelihood forever (Joel 4:20).”

Being a student of the Scriptures, Shaftsbury knew that the Bible foretold a return of the Jews to what was then called Palestine. Being an astute politician, he was also aware of Napoleon’s plan that never came to fruition. Although it is almost certain that Shaftebury’s mission was prompted more by his Judeo-Christian worldview – which was not necessarily widely held at the time – nonetheless, he also saw the same political and economic advantages for the British Empire.

Our purpose is not to question motive, however, so much as it is to promote awareness that Lord Shaftesbury’s commitment to the Word of God, not his use of it to his political advantage, drove him to use his influence to whatever extent he could to promote the idea of creating a homeland for the Jews. He wrote to the British Prime Minister that, “There is a country without a nation; and God now, in his wisdom and mercy, directs us to a nation without a country. Is there such a thing? To be sure there is, the ancient and rightful lords of the soil, the Jews!”

Perhaps because of both his Christian and political connections, Shaftesbury gained support from both spheres. While those strange bedfellows engendered the usual watered-down results of the inevitable outcome of trying to accomplish a singularly beneficial outcome from divergent agendas, the result, nonetheless, paved the way for the Balfour Declaration and the eventual establishment of the State of Israel.

We do well to understand that the LORD has turned the hearts of men and women of influence and other visionaries to lay the foundation for the nation of Israel. Let us never forget what Solomon said in Proverbs 21:1 – “The king’s heart is in the hand of the LORD. Like the rivers of water, He turns it wherever He wishes.”