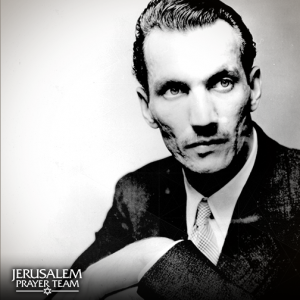

Jan Karski was named Righteous Among the Nations and given Honorary Citizenship in the State of Israel in 1982 at the age 68. Karski’s story may not be as well-known as others, like Schindler, but, it in a taped interview in 1996, four years before his death, he was still unable to tell even a part of his story without shedding tears that revealed a broken heart.

Jan Karski was named Righteous Among the Nations and given Honorary Citizenship in the State of Israel in 1982 at the age 68. Karski’s story may not be as well-known as others, like Schindler, but, it in a taped interview in 1996, four years before his death, he was still unable to tell even a part of his story without shedding tears that revealed a broken heart.

Understandably, his heart was broken by the atrocities that he had personally witnessed beginning to unfold perpetrated on the Jewish people in his Polish homeland. But this was not his greatest heartache nor the one that inflicted the greatest personal pain. It was the one that he called the Second Original Sin. He did not mean the Holocaust. He was referring to the, “self-imposed ignorance, or insensitivity, or self-interest, or hypocrisy or heartless rationalization,” that caused his mission to fail.

Karski’s mission was not to save a Jew. It was not even to save some Jews. It was to save all of them. He said, “The Lord assigned me a role to speak and write during the war, when – as it seemed to me – it might help. It did not.” Therein was his heartache. Having seen first-hand how the Jewish people were suffering under the Gestapo in Warsaw, he understood that nothing would stop Hitler from completing his Final Solution, unless it came from outside the countries over which he had control. He determined to expose the travesty to the entire world.

At great peril to himself and those who helped, he made his way across Europe in 1942 to Great Britain and, ultimately, to the United States intending to appeal to the highest levels of leadership for the help the Jews so desperately needed. Indeed, he was received by some of the most influential people in both countries, where he produced graphic and startling evidence “exceeding everything fantasy can picture.”

In Washington D.C., he met with President Roosevelt’s closest Jewish advisors. Those meetings were where his heart was crushed. Despite being politely received, he found that, almost without exception, his words had fallen upon deaf ears, even to the extent that Felix Frankfurter, himself a Jew and a Supreme Court Justice, told Karski, “I am unable to believe you.”

It is difficult to imagine the frustration of the messenger whose report would not be believed and whose hopes were miserably dashed. But, if there could be a horror more imaginable than the Holocaust itself, it might have been the one that Karski ultimately suffered when he read the news reports after the war that “the governments, the leaders, the scholars, did not know what had been happening to the Jews. They were taken by surprise. The murder of six million innocents was a secret.”

Karski, on a mission to warn the world and save the Jews from unspeakable abominations, came to understand how many of the Old Testament prophets agonized when no one would listen. The more he tried, the more he was rebuffed, but the more he also learned to love the Jewish people.

In his later years, Karski called himself a Christian Jew. His wife’s entire Jewish family died in the concentration camps. Karski’s love for the Jewish people endured as long as he lived.