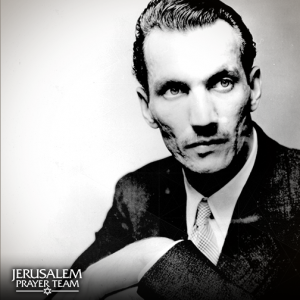

Raoul Wallenberg was born into a well-to-do Swedish family in Stockholm in 1912. He studied architecture at the University of Michigan, where he graduated with honors in 1935. Of the many honors this brave Swede earned over the years, the greatest were, perhaps, being officially named as one of the Righteous among the Nations in 1963, being awarded honorary Israeli citizenship in 1987 and honorary American citizenship in 2008.

Raoul Wallenberg was born into a well-to-do Swedish family in Stockholm in 1912. He studied architecture at the University of Michigan, where he graduated with honors in 1935. Of the many honors this brave Swede earned over the years, the greatest were, perhaps, being officially named as one of the Righteous among the Nations in 1963, being awarded honorary Israeli citizenship in 1987 and honorary American citizenship in 2008.

Among the tens of thousands of Hungarian Jews that Wallenberg is credited with rescuing was a young boy named Tom Lantos, who eventually became a U.S. congressman. It was he who sponsored Wallenberg’s honorary U.S. citizenship. He wrote, “During the Nazi occupation, this heroic, young diplomat left behind the comfort and safety of Stockholm to rescue his fellow human beings in the hell that was wartime Budapest. He had little in common with them. He was a Lutheran; they were Jewish. He was a Swede; they were Hungarians. And yet, with inspired courage and creativity, he saved the lives of tens of thousands of men, women and children by placing them under the protection of the Swedish crown.”

After having spent several years working in South Africa and in Haifa, he returned to Sweden where his business travels took him throughout Nazi-occupied Europe, including France, Germany and Hungary. During those trips, he became aware of the cruel treatment of the Jews under the Nazi regime. In June 1944 he was inserted into the growing crisis in Hungary, ostensibly as the leader of the Swedish legation there, but with a directive to help rescue Jews whose extermination was being planned by Adolph Eichmann. By the time he arrived, nearly half of the Hungarian Jewish population had already been transported to concentration camps.

Despite an original plan to extract as many as 700 Jews by use of diplomatic passes, and moving with a passion that far outweighed that of Eichmann, Wallenberg managed to rescue 120,000 Jews, more than half the remaining population, from Eichmann’s dastardly plans. Before he left Sweden, he had appealed to the highest levels of the Swedish parliament and to the monarchy to gain permission to have a free hand to take whatever actions he saw fit, without the encumbrance of bureaucratic interference. That permission was granted, and he took full advantage of it.

Raoul Wallenberg was far more than a paper-pusher. He personally intervened on behalf of the Jewish people and directly interfered with Eichmann’s plan. He hired hundreds of “employees” and hid hundreds more in “Swedish libraries.” He built houses, outside of which were hung Swedish flags, and which he declared to be Swedish territory in which hundreds more were hidden.

His heroism and his cause were publically evident when he would run atop already loaded railcars, stuffing diplomatic passes that exempted the bearers from being relocated. He would then demand that the soldiers open the doors and release into his custody any who had a pass in their possession. It is said that, when the German soldiers were ordered to shoot him as he ran across the cars, they deliberately aimed high in admiration for his courage.

In January 1945, Wallenberg was escorted by the Russian military to an unknown destination. Before he left, he told an associate that he was unsure whether he was going as a guest or as a prisoner. He was never heard from again.

We may never know the rest of the story, but we do know this, that “there is no greater love than a man who would lay down his life for his friends.” Be it known, by the compassion and actions of Raoul Wallenberg and thousands like him, then and today, that there are many righteous among the nations who are friends to the Jews.